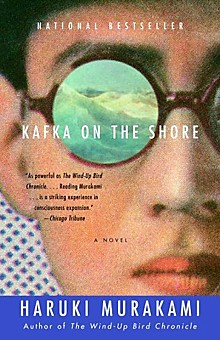

“”Kafka on the Shore,”” Haruki Murakami’s latest book, is about two outcasts who find themselves plunged into bizarre metaphysical quests. Neither really understands what they are looking for or even why they are trying to find it, but both somehow understand that the quests are important.

Murakami, author of “”Norwegian Wood”” and “”The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle,”” is one of Japan’s best-known writers. His style is relatively simple and realistic, but his stories blend a contemporary setting with freewheeling, surreal fantasy.

“”Kafka on the Shore”” shifts back and forth between two distinct narratives, one in first person, the other in second person. The effect is rather like reading two books at the same time; they move along at about the same pace, but their tone is wildly different.

The first story is about a 15-year-old boy who calls himself Kafka, who runs away from home for reasons that do not become clear for a while. Indeed, Murakami’s willingness to leave out obvious plot points until later is one of his most unusual traits.

“”I’ve built a wall around me, never letting anybody inside and trying not to venture outside myself,”” Kafka tells us. He doesn’t let us in either; like a hard-boiled detective, we don’t find out much about him until he confides it to someone else. Kafka is not exactly likable, or even necessarily sympathetic, but Murakami manages to keep us interested in what happens to him.

His father, he eventually reveals, told him that he would live out the curse of Oedipus: to murder his father and sleep with his mother – with his sister thrown in for good measure. But he hasn’t seen his mother or his sister in years, and he has no idea even what they look like. Almost any woman he meets could be either of them.

One night shortly after running away, he passes out and wakes up lying on the ground covered in blood – someone else’s. A few days later, he learns that his father has been murdered, and that the police are looking for him. He knows that he couldn’t have done it – or could he?

Kafka’s troubles only increase. After wandering around Japan for a while, he winds up working at a library, where he falls in love with a girl his age.

The trouble is, this girl happens to be a ghost. Ghosts flicker through the pages of this book, some of them dead and some, bafflingly, still living.

The second of Murakami’s protagonists is an old man named Nakata, a once-brilliant student who suffered a mysterious accident in 1944 and not only lost his memory but has been unable to learn anything since.

But the accident also left him with a few unusual skills, like the power to make it rain fish (he carries an umbrella around with him for just this reason) and the ability to talk to cats.

Nakata’s conversations with cats start his story off on a light, amusing note, until a search for a missing cat leads him to a murderous confrontation with a mysterious man who calls himself Johnnie Walker.

This man, we quickly guess, is Kafka’s father, but he also seems to be a sort of evil spirit. The scene in which he appears is so surreal that it is difficult to take literally. Murakami blends reality with fantasy so smoothly, though, that we barely think to question it.

Rating

8/10

After that, Nakata sets off across Japan in search of something – he doesn’t know what, but he’ll know it when he sees it.

The effect of all these bizarre plot shifts is sometimes startling but never really jarring. Murakami somehow manages to convey the mood of a dream: its fluid, serene tone; its violent mood changes, and its feeling that some overriding point is frustratingly close yet just out of reach.

Another good comparison might be to a folk tale, in which raining sardines and talking cats are nothing remarkable.

The two plotlines wind around and around each other like a double helix, often threatening to touch but keeping their distance until they finally collide. The stories unwind with a dreamy intensity, at once meandering and gripping, keeping their secrets until the end.