As politically-involved UA students flood Tucson-area polls today, it’s likely that few have any idea that an even greater election fever swept campus 50 years ago, as the unsuccessful southern Arizona-based drive to defeat Proposition 200 resulted in the transformation of Arizona State College, Tempe, into Arizona State University.

“”It was a big campaign – we really went all out for it,”” said Stella Johnson, an 1950 graduate of the UA and wife of former student union, UA Alumni Association director and vice-president for university relations Marvin “”Swede”” Johnson. “”There was a lot of animosity. … (ASU backers) really felt like we were holding them back.””

The pages of the Arizona Wildcat – which didn’t begin daily publication until 1965 – were filled with invective against the proposition, which was placed on the Nov. 4, 1958 ballot largely through the efforts of students and backers at the future ASU.

The petition drive to get what was to become Proposition 200 on the ballot got off to a slow start, prompting a May 9, 1958 Arizona Wildcat editorial denigrating the effort.

“”Why are the ASC students so apathetic to their great crusade when work has to be done?”” the editorial titled “”Questions”” asked. “”Maybe they are beginning to understand that atomic reactors and television stations mean more to higher education than nationally-ranked football teams.””

The petition drive picked up speed, however, and when petitions were finally filed, backers of the name change had gathered more than 64,000 signatures, when only 29,000 were needed to qualify the initiative for the ballot.

When classes resumed in the fall of 1958, the statewide campaign was in full swing, and UA students joined in the effort to defeat the measure. The Arizona Wildcat covered the campus efforts under its first-ever color headline, “”‘Anti-200’ Movement Started.””

The article quoted an anti-200 brochure as saying: “”In the matter of financial support, the present single university (UA) is seventh from the bottom among the 48 principal state universities, and … at the absolute bottom of 50 state land grant institutions.

“”The net effect of attempting to support two state universities would be either to increase the tax rate by more than 50 percent or to accept for the foreseeable future, throughout Arizona, sub-mediocrity in publicly supported university education,”” the article concluded.

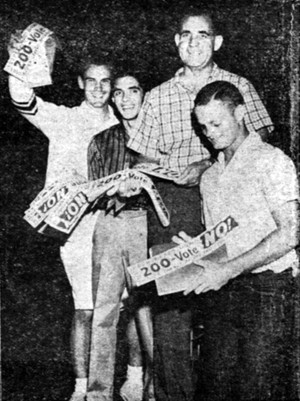

Tucson community leaders, organized as Citizens for College and University Education, were joined by fraternity and sorority houses who competed against one another to sell the most $1 bumper stickers. The student union activities board sponsored an anti-200 dance with the theme of “”Deep in the Heart of Taxes,”” debates on the merits of the issue were broadcast over Tucson and Phoenix televesion stations and the Homecoming issue of the Arizona Wildcat exhorted university alumni to spread the anti-200 message across the state.

The final week before the election saw more than 1,000 fraternity men canvass the Tucson area, obtaining more than 10,000 signatures against the proposition, but in the end, the Pima county effort proved too little against the will of the rest of Arizona. The initiative was defeated easily in Pima county, with only 10 percent of voters in favor, but statewide the initiative passed by a 2-to-1 margin.

The passage of the proposition established the framework of today’s system of universities in Arizona, a framework that is now being tested by the prospect of nearly unprecedented cutbacks in state funding.

“”One thing that is basically different in Arizona relative to other states is that we have a larger share of our students educated in large research universities, which is traditionally more expensive,”” said John Cheslock, associate professor in the Center for the Study of Higher Education at the UA. “”The questions we need to ask are: How many universities do we want, and how much is the state willing to pay? And the one answer that is pretty clear is that Arizona is not willing to pay more than other states.””

The 1958 debate over the future of the Tempe school presaged a report written just three years ago by consultants hired by the Arizona Board of Regents. The report, whose recommendations have largely gone unheeded, proposed a tiered system of schools, with the UA and ASU at the top, NAU joining two new regional schools to be created out of ASU West and UA South and the state’s community college system providing the foundation.

“”For the size (of state) that we have, it’s unusual to only have 3 4-year schools, and 2 of the 3 are research schools that in many areas try to be nationally competitive,”” Cheslock said.

In the end, neither of the scenarios envisioned by ASU opponents came to passÿ- tax rates did not increase by 50 percent, and the UA continued to succeed – but the real impact of the change 50 years ago will never be known.

“”The real question is, if it didn’t happen this way, what way would it have happened?”” Cheslock asked. “”Would there be one clear research university, and maybe more (smaller teaching) universities? There’s no way to know.””

Although the backers of the new university were successful, a divide between the supporters of the two institutions remains to this day.

“”It was a standing fight every year in the legislature,”” Johnson remembers. “”They tried to take everything in the world from us. There’s still a lot of bitterness – we still don’t like ’em.

“”I still call them Tempe half the time – not on purpose – it just comes out.””