UA student organization Paws for the Cause, has said goodbye to another batch of freshly-trained guide dog puppies. While guide dogs perform an important task, it isn’t the only necessary job that canines can hold on a college campus. Many dogs on campus function as therapy dogs, calming stressed or anguished students. But what is the science behind the therapeutic affect of man’s best friend?

Therapy dogs are a common sight on the UA campus, their presence only increasing during stressful times like finals week. Dog Days with the Dean is a bi-weekly event allowing students to drop by the Robert L. Nugent building and pet friendly dogs.

The idea that dogs may have a psychological benefit is not new.

“There’s been thinking about this since the seventies,” said psychology graduate student Netzin Steklis. “It has been observed that, somehow, they make a difference.”

Netzin is an adjunct research specialist at the UA and co-chair of the Human-Animal Interaction Research Initiative (HAIRI), an organization that studies the relationship between humans and animals. The organization has conducted several studies on therapy dogs, equine therapy and other types of animal-assisted therapy.

There are many documented benefits of therapy dogs. Their presence has been shown to lower heart rate, increase the production of oxytocin and reduce stress. Studies have demonstrated that this effect is limited to a living, breathing canine and that a toy dog does not have the same benefits. Dogs have also been shown to be more comforting to a distressed individual than a friendly person.

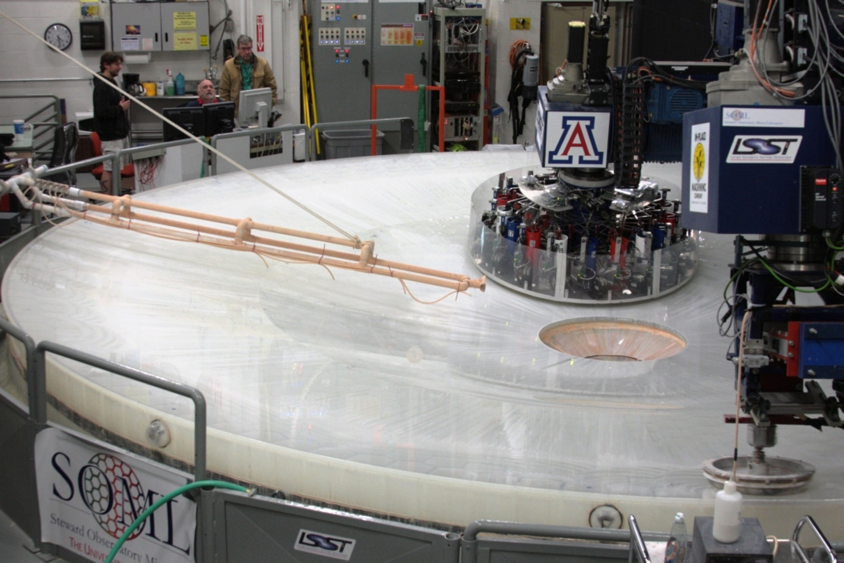

RELATED: Featured Science: Mirror lab builds cutting edge telescope parts

On a college campus, this sort of positive effect can be very important. Statistics are steadily rising for college students diagnosed with and treated for both anxiety and depression. While there are many sources for mental help at the UA, Netzin believes that animal therapy is another possible route that should be taken into consideration.

“This idea of therapy dogs on campus has spread across the U.S.,” said UA South psychology professor H. Dieter Steklis, the other co-chair of HAIRI and UA South anthropology program director. “At the Yale library, you can check out a dog for an hour to relieve stress.”

The science behind therapy dogs is faulty, however, and occasionally difficult to prove.

“It is not the best controlled, in the scientific sense,” Dieter said. “Part of this is because it’s young—it’s new.”

One study found that, out of over 400 studies on the benefits of therapy dogs, only 10 met scientific standards.

RELATED: Reminders of death increase performance in sports

There is also a large difference between a therapy dog and a service dog. A service dog is specifically trained for whatever their task is; typically, the dogs brought into the campus libraries during finals week are service dogs. A therapy dog often isn’t trained or certified, much like an emotional support dog. This means that a therapy or emotional support dog is unable to enter many of the same places that a service dog can.

There are legal issues relating to emotional therapy dogs and college campuses, especially when it comes to dorm life, where any pet—besides a fish—is not allowed.

Despite this, Netzin said that there is still a large demand for therapy dogs in everyday life. “Emotional therapy dogs are shaking up campuses,” she said.

Both scientists consider the science of therapy dogs to be in its infancy stage, with room for growth and development, which inspired them to enter the field.

“We would like to see more evidence,” Netzin said. Through HAIRI, the Steklis’ may be able to find the evidence that supports the positive benefits of therapy dogs, especially in a college environment.

The researchers current projects include a study on how equine therapy can benefit children with autism and how dog therapy may be used in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) in hospitals. They also co-teach a general education class on human-animal relationships.

Follow Nicole Morin on Twitter.