Strolling through the Tucson Museum of Art’s exhibition, “”Ansel Adams: A Legacy,”” provides visitors with a renewed view of the photographer’s life through his many famous prints, and an opportunity to see the textured graininess and rich tones in their intended sizes.

It’s easy to forget how modern the work of Ansel Adams can be. Natives of the Southwest and especially of Tucson are constantly inundated with reduced prints of his well-known landscape photographs. His techniques, approach to subjects and theory of visualization have been absorbed so thoroughly into contemporary photography that the experience of confronting his work comes as a surprise.

It’s difficult to overstate the importance Ansel Adams had on photography and his influence on the art world. In addition to being one of the seminal photographers of the 20th century, Adams was an educator and advocate on behalf of photography and the environment. His photographs provided visual ammunition for arguments to preserve the national parks and their surrounding wildernesses. Adams was also responsible for the creation of the UA’s Center for Creative Photography and its unparalleled collection of his work.

The exhibition begins with one of Adams’s most striking and famous photographs, “”Aspens, Northern New Mexico (vertical).”” This 1958 photograph is larger than some of the portraits on display. It towers over incoming visitors with its ghostly visage of aspen trunks floating in a world removed from humanity. It serves as an apt representation of Adams’s efforts to find the abstract in nature.

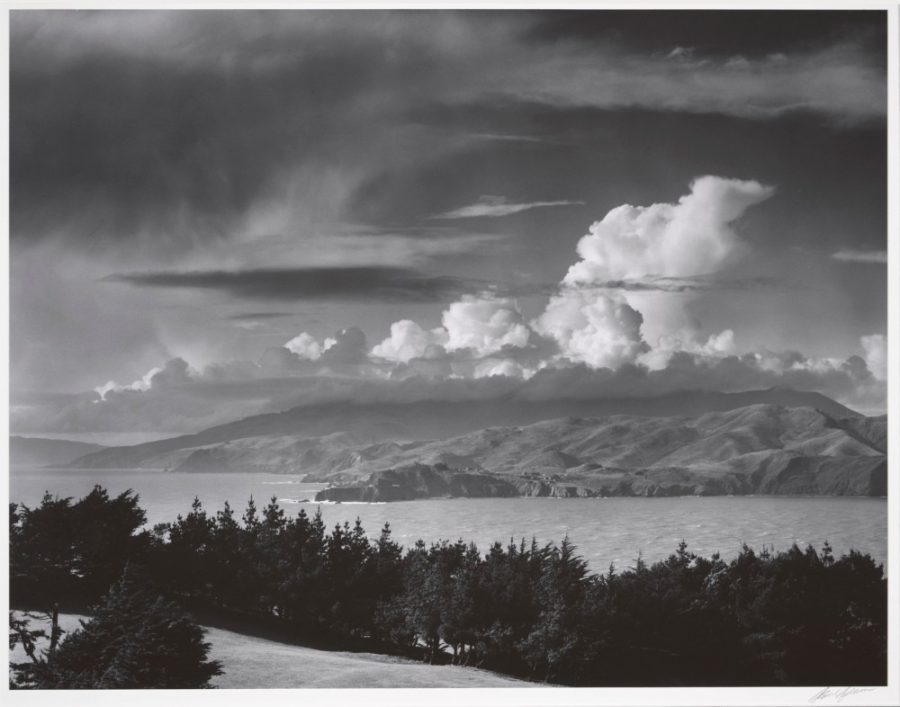

As the exhibition gently slopes its way downstairs, each set of photographs represents different aspects of Adams’ life and become increasingly abstract. Some of his lesser-known photographs show the overwhelming presence of nature in the face of urban areas, as in 1959’s “”The Golden Gate.”” The famous bridge of his birthplace is dwarfed by massive white and gray clouds as it becomes just another feature of the hillside landscape.

Adams’ love of music — he was trained as a pianist — reveals itself in many of his photographs. There is a silent visual rhythm that comes through how he captured the subject through his lens. The 1940 San Mateo County Coast, Calif., sequence is a series of five photographs of a beach from the top of a cliff. Viewed one after another, the dark waves vary in shape and tone in accordance to its own tempo, and the only constant is the beach shore. In the 1953 “”San Francisco From Twin Peaks,”” the city is splayed out across the photograph. The hilly land gives the city a swing that is anchored by a street that bisects the view.

There is a surprising, yet appropriately small, section devoted to his portraits of friends and influences. Subjects include his friend and fellow photographer Edward Weston, artists Georgia O’Keeffe and Jose Clemente Orozco. Despite its air of formality, the arresting image of Tony Lujan, governor of the Taos Pueblo, stands out from the series. As he does with his other portraits, Adams takes a close shot of Lujan who is clad in traditional clothing and looks into the camera with quiet pride.

The exhibition ends with photographs mostly taken during the late 1960s, in which it can be difficult to discern the original landscapes. In a sense, these abstracted landscapes draw a parallel to traditional and modern Chinese landscape paintings. The artist’s conception and interpretive vision of what’s there matter more than a realistic duplicate of the subject.

As with those paintings, small reproductions cannot do justice nor compare to the power of the original artwork. “”Ansel Adams: A Legacy”” reminds us that calendars and poster prints are nothing like the real thing.