Experts explain the lingering effects of the pandemic on mental health

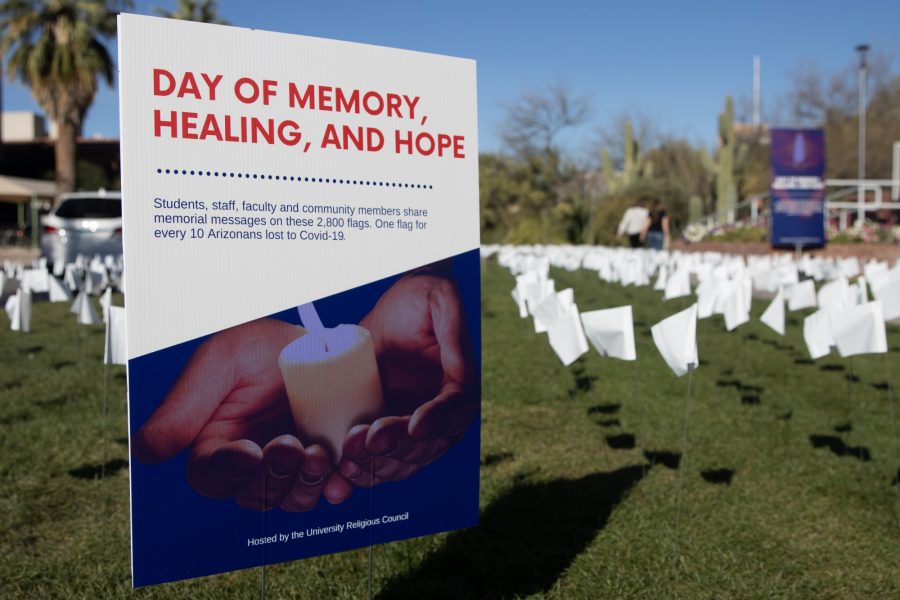

The University Religious Council hosted a day of “memory, healing and hope” to memorialize the lives of Arizonans lost to COVID-19 on March 23, 2022, on the University of Arizona Mall in Tucson, Ariz. There were 2,800 flags placed on the lawn, some with handwritten messages, with each flag representing 10 Arizonan lives lost to the virus.

March 14, 2023

It’s difficult to fully comprehend the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on any aspect of society, much less on a topic as complex as mental health. But as the U.S. reaches its three-year anniversary of the beginning of lockdown, it’s clear that the impact of this period isn’t going away immediately.

Lia Falco, who holds a doctorate in educational psychology, is an associate professor in the University of Arizona College of Education. She spoke about how COVID-19 brought mental health to the forefront of society.

“I think it really shined a big bright light on mental health challenges that maybe have always been present for a lot of students, but perhaps became more amplified during the pandemic,” Falco said.

According to Dr. Noshene Ranjbar, an associate professor of psychiatry at the UA College of Medicine – Tucson, the mental health impacts from the pandemic are complex. She explained the different impacts of the pandemic on the mental health of students, including learning difficulties, social isolation and substance abuse, along with the grief and loss caused by illness and death.

Ranjbar called for more systems in place to help people and more education about taking care of ourselves.

“Those aspects of building community and building a sense of human connection are absolutely essential to addressing the impact of trauma,” Ranjbar said.

Leslie Ralph, who has a doctorate in clinical psychology, is the coordinator of mental health promotion and communication for the UA’s Counseling and Psychological Services. Ralph discussed how the different phases of the pandemic impacted students, from the isolation of quarantine to the tensions of readjusting to society and in-person education.

“Challenges that students faced during that time with school, changes in their GPA, difficulty meeting demands, starting programs in the middle of the pandemic, has then had lasting effects on their ability to feel connected and their ability to thrive in those programs now,” Ralph said.

But as the pandemic exerts less and less of an impact on our daily lives, there has been important progress. Ralph has personally seen positive changes at the UA in terms of more awareness around mental health.

“I just see a lot of departments within the university starting to ask questions about how they can support mental health,” Ralph said.

Dr. Trung (Jack) Duong is a fourth-year psychiatry resident at the UA College of Medicine – Tucson. He has noticed the increase in the need for mental health care, with more students reaching out for help with depression, anxiety and ADHD since the pandemic began. He has also noticed that there aren’t enough available psychiatrists, psychologists and counselors to meet this demand.

“There is an increase in need even after the pandemic and I feel like the shock wave might continue for many, many years to come,” Duong said.

Along with the learning difficulties from the pandemic, Ranjbar also mentioned the impact of technology on college students as harmful to mental health.

“Our brains are not wired to be in front of blue light and screens 20 hours of the 24 hours,” Ranjbar said.

While recent years have seen an increase in young people discussing mental health openly, the downside is that many people aren’t getting information from reliable sources or getting legitimate help.

“We need to put more of our money and spending into mental health resources,” Duong said. “Even with Telehealth, we need to make sure that we expand internet access.”

Accessibility remains a major problem. Falco pointed out that the primary barrier that keeps people from accessing therapy isn’t stigma, but accessibility with regard to time, transportation and money.

Falco has seen increases in mood disorders in K-12 students as well and spoke about the ongoing crisis in mental health affecting adolescents and college students.

“We’re still not yet, as researchers, able to say fully whether that’s a direct result of the pandemic or whether it’s all of these related factors that have just converged around the pandemic,” Falco said.

But she explained that this time caused a “collective trauma” that affects both individuals and society overall.

“That will be felt for many, many years to come,” Falco said.

The first step to fixing this problem, she continued, is acknowledging these issues instead of rushing a return to normal. She also spoke to the necessity of making services more equitable and accessible.

“We can’t have a conversation about mental health without talking about how hard it is to get help,” Falco said.

The omnipresence of Zoom may have been harmful for some students, but in terms of mental health care, it’s been revolutionary.

“We’d been talking about offering Telehealth for years,” Ralph said. “It was hard to make it happen logistically, and then we did it overnight basically.”

Telehealth has been a major improvement in making mental health care accessible, but there are still many barriers to making quality care available to everyone as college students continue to struggle with mental health issues at high rates.

“It is a crisis,” Ranjbar said. “It’s both the impact of the pandemic but also the fact that our healthcare system is not optimal.”

Ranjbar is critical of our current infrastructure, but also confident that progress is coming, and that there is reason for hope.

“No matter how stressful and traumatic something like a pandemic can be, it’s also fertile ground for growth and innovation and learning and maybe becoming even stronger,” Ranjbar said.

Follow Erika Howlett on Twitter