Guido Contini is a character who could make Casanova rethink what the woman means to him. In “”Nine,”” Daniel Day-Lewis (“”There Will Be Blood””) plays Contini, an Italian director in the 1960s balancing precariously between what he perceives as reality and cinema, fidelity and adultery and genius and insensibility as he scrambles to put together a movie he has not yet created. A man untouchable to everything in the world — except women.

Day-Lewis’s portrayal of Contini exemplifies director Rob Marshall’s (“”Chicago””) characteristic use of subtlety. From the start of the film, nothing is ever purposefully expressed, but continuously, inferentially layered. In the press room coyly joking with reporters, Contini constructs himself as a man entirely independent of others, unaware of responsibilities, deadlines and even his own talent.

As a man only aware of his deep-seated devotion to the female sex in all her curves, power and inspiration, Contini comes to life for a brief moment as these traits culminate, at least for the time being, in Stephanie (Kate Hudson), a fashion reporter from America.

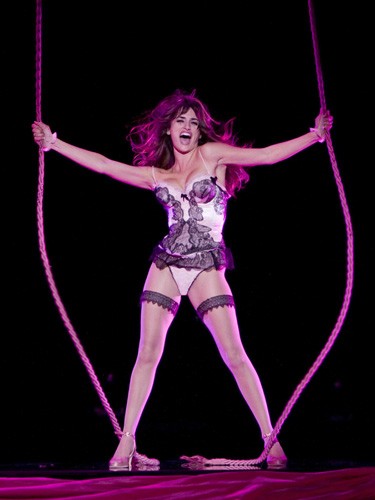

Marshall maintains teeming sensuality just within the lines of artful rather than raunchy, even as Contini’s mistress Carla (Penélope Cruz) rolls and stretches across the stage, hands wandering up and down her bodice and fishnet tights.

Contini’s past, present and genius bleed together in a surreal kind of autobiography, making reality something as intangible as love for a man whose life has been dedicated to celebrating many women, but never loving one completely.

With a cast boasting Nicole Kidman (the starlet of Contini’s unwritten film), Sophia Loren (Momma), Judi Dench (his costume-making confidant) and Marion Cotillard (Contini’s jaded wife), the one that will take your breath away is none other than Stephanie Ferguson, aka Fergie.

With wild hair and fists full of sand, Fergie as Saraghina introduces a young Contini to the world of sexuality, haunting the screen long after she’s left it. “”Be Italian”” drips with a richness rare to even the best film adaptations.

Taking advantage of dimensions unavailable to the stage, Marshall slinks between scenes, hiding the camera behind stone walls and stage constructions, creating a profound intimacy between audience and musical. Original writers Arthur Kopit, Maury Yeston and Mario Fratti should be at ease — screenwriters Michael Tolkin and Anthony Minghella only polish this gem of a musical until it shines.