Harold H. Jones was born in Morristown, N.J. He worked his way through high school at the local A&P, stocking the candy aisle. When it came time to pursue a higher education, Jones opted for the Newark School of Fine and Industrial Art; a school that offered certificates rather than degrees. He was a painter, so, naturally, he studied painting. His parents didn’t think art school was a good idea, but he went anyway.

“”I had a teacher. I took photography as an elective as a lot of people do. I was a painter, I had studied painting and so it was that same semester it was taught by professionals from New York City. He was teaching this class I was in, and I made some pictures and did the work. He told me I had sense for it,”” Jones said.

Forty-four years later, his photographs, photo drawings and paintings have been exhibited in hundreds of galleries, and he is credited with being a founder of the LIGHT Gallery in New York and the founding director of the Center For Creative Photography, among other accomplishments.

Maybe art school wasn’t such a bad idea after all.

I met Jones on Feb. 10, right before it started raining. I had been riding my bicycle in circles for 15 minutes before I finally decided to call him and admit I could not find his house. After he pointed me in the right direction, he asked that I please call him Harold. I don’t remember if I ever did. It’s hard to call someone anything when they have certain accomplished calmness about them as he does. So when I arrived, I locked my bike to the wrought iron fence and walked up the concrete steps that led to his front door. I thanked him for welcoming Arizona Daily Wildcat photographer Tim Glass and me to his home and called him neither Harold nor Mr. Jones.

Willow, his small dog, barked for the first 20 minutes we toured the house, but it hardly distracted from the pictures that hung from almost every wall within the house. The complete basement beneath the house held his entire collection, a dark room and a laundry room. Up the stairs that were too high and narrow to be built in a modern home, were his paintings and a small wall dedicated to work of family and friends.

After graduating from Newark School of Fine and Industrial Art in 1963, Jones enrolled at the Maryland Institute of Art in Baltimore. He had expected to study painting, but instead ended up studying photography.

“”I didn’t have a very good photography teacher at the Maryland institute, actually. But I got to know a historian and a guy who was a cultural historian. I didn’t know I liked history, so I did learn something there,”” Jones said.

He obtained a graduate degree from the University of New Mexico. Jones had always tried to imagine what the Southwest would look like. When he arrived, the sun’s presence astounded him. Some of his first photographs were of animal shapes and shadows on the ground. Thanks to a helpful professor, he was able to get a prestigious internship at the George Eastman House during school. It was at this same gallery that he was offered his first job as an assistant curator upon graduation. During the five years he worked there, he met his wife Francis.

“”I never had to really look for a job. I’ve helped so many people look for jobs. One things kind of leads to another, not on purpose. I went, I did a good job, I worked hard. I thought that was what I was supposed to do,”” Jones said.

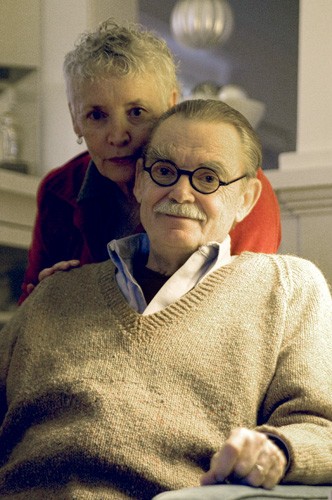

We paused as Francis cut in to say she was going to leave for the store before the rain started. Tim asked for a quick picture of Harold and Francis together prior to her departure. She obliged and said, “”The women behind the man.”” Jones laughed and said, “”Amen to that.””

From the George Eastman House on, life unfolded leading Jones to New York then Tucson. He held the position of director of the CCP for two years before stepping down. He decided that teaching would keep him home with wife and two young daughters. Jones retired from teaching at the UA after only five years.

Ultimately, his career, rather than extending from a series of heart-wrenching choices, fell into place all on its own. He has left his good name here at the UA.

“”I think that Harold has been a giant in the field of photography, thanks to his leadership in the LIGHT Gallery and establishing the Center for Creative Photography. He has made astounding contributions to field and we are lucky to have him here at the University of Arizona,”” said Carla Stoffle, dean of the libraries and current interim director for the Center for Creative Photography.

Jones said he keeps his technique fresh by heading out to different places and just taking a couple hours to shoot. His photo drawings in particular come from the orphan prints that don’t stand up to the standards he had for them.

“”Sometimes, it’s about solving the picture. The photo drawings come from orphans, pictures I print that I think are going to be great. With the photo drawings, I make a picture work perfectly. Like when you write something and you think it’s going to be really good that day and then the next day you wonder what you were thinking — it’s that same thing. I would have a photograph I thought was really great, but then a week later it was not unfolding, it was not doing anything. I used to tear them up and throw them away. I started saving them. This is a point where I wanted to get back to painting and drawing,”” Jones said.

The photo drawings are prints that are altered by pen and ink, acrylic paint, or, in Jones’s experience, sandpaper. Jones values the technical precision it takes to make a solid and beautiful print.

When asked what the most prominent elements of his work were, he said, “”I guess one part of my work is about storytelling, the other thing is the nature of light.””

I left Jones’s house that day in the rain. As I unlocked my soaked bike, I couldn’t help but think that maybe the recipe for a fortunate life included simpler ingredients than I had imagined.