Your hands are shaking. Your palms are wet. You nervously await the start of your run. Dirt flies up with each step you take and glows in the air from the strong, hot sun above.

Sweat drips from your face as you fly faster and faster. You may be moving at high speed, but it feels like time is standing still.

These are the emotions every runner goes through during a race. The only difference in this race is that you’re not running for fun – you’re running for your life.

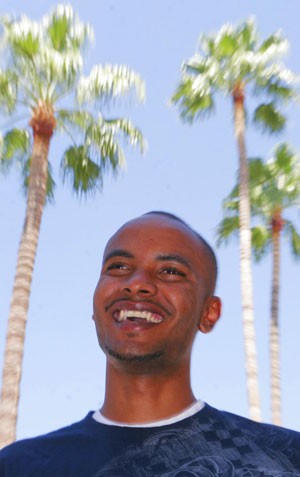

Arizona sophomore cross country runner Mohamud Ige knows all too well what it means to run for his life.

Ige was born in Somalia and raised in Kenya. He was surrounded by violence and hatred and bounced from refugee camp to refugee camp. Ige didn’t just run for fun; he ran to survive.

With a current population of more than 9 million, a country being ravished by disease, fighting and droughts and a Human Development Index – measured mostly by life expectancy, literacy and education, things foreign to the majority of Somalians – that is so low it doesn’t even appear on the list of world rankings, Somalia is in nothing short of bad condition.

In Somalia, his father was assassinated, though Ige was spared from the sight. When he was 2 years old, Ige’s mother, Khadija sold jewelery to move out of Somalia to nearby Kenya. Ige then spent the next six years in refugee camps.

Living life is an everyday struggle in refugee camps and people are lucky to make it out without any problems, Ige said. Even though the camps are supposed to help people get through their daily struggles, living in these conditions is no walk in the park.

“”You felt isolated from the outside,”” Ige said. “”We were kept in this cage and had a boundary of where we could go. If you stepped outside the boundary, you either sacrificed not coming home or sacrificed your life.””

UA cross country head coach James Li expressed how traumatic living in a refugee camp must have been.

“”It’s not a place you want to grow up. There’s no feeling of security which is important for a child,”” Li said. “”He was against all the odds and the chances of achieving success were not very good.””

Li continued to describe Ige’s troubling experience by comparing it to the movie “”Black Hawk Down,”” with all of the tribal violence.

Living in a small clay adobe building and sharing a bedroom with seven people, it is clear how tough growing up must have been.

But for Ige, simply making it out of the refugee camps wasn’t enough. He went above and beyond and has transformed himself into a successful NCAA long distance runner.

“”He has persevered and worked through all adversities,”” Li said.

Most people from his hometown would love to hear of their old neighbor becoming a college runner, Ige said.

“”People from home would have a big smile. They are really proud of me,”” he added.

After all Ige has gone through, he owes all his success to his mother because, as he put it, “”She sacrificed everything for my life.””

Because of everything his mother did for him, Ige feels that being a successful runner is a way of “”paying her back.””

One thing that is so remarkable about Ige is his work ethic – not only on the team, but also in the classroom.

“”He is definitely doing everything he can, especially in school,”” Li said.

When he moved to America in 1997, Ige didn’t know what cross country was. He didn’t understand the concept of the sport at all. In fact, Ige’s only familiarity with running dated back to the refugee camps, when he would kick a soccer ball around with his friends – or when native Kenyans would chase him.

“”Once you step out of the gate, you’re on your own,”” Ige said. “”It’s their territory so you have to be prepared to run.””

The importance of running goes beyond great exercise for Ige. It’s also symbolic of where he came from.

“”I can represent who I am and also represent my country of Somalia,”” Ige said.

What’s more, being a collegiate athlete is meaningful because there are few professional runners from Somalia in the world today.

“”Only maybe five,”” Ige said. “”You think about what you’ve gone through and to represent who you are tells you what kind of character you have. Growing up wasn’t easy so it’s an honor to be a Division I athlete.””