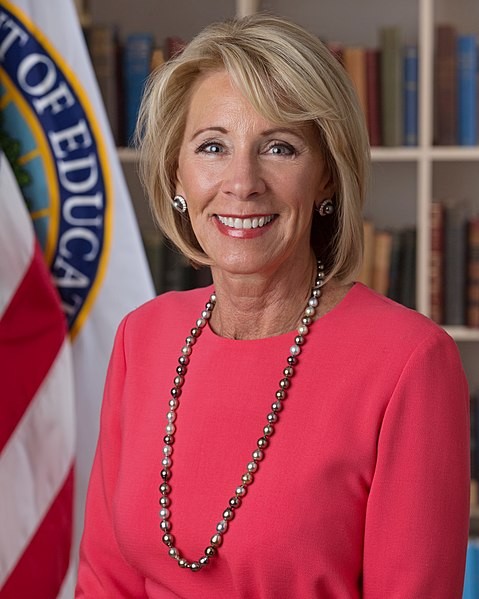

Last September, the U.S. Department of Education, under Secretary Betsy DeVos, released a new set of Title IX guidelines, replacing requirements put in place by the Obama administration to combat sexual misconduct on college campuses, marking the beginning of the Trump administration’s ongoing efforts to reform Title IX rules.

Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 prohibits sex discrimination, be it by exclusion or denying the full benefits of a program on the basis of sex in all education activities receiving federal funding. This includes college campuses like the University of Arizona.

“This interim guidance will help schools as they work to combat sexual misconduct and will treat all students fairly,” said DeVos in a September press release announcing the new changes.

The new guidance is the first step in a larger effort by the Trump administration to overturn Obama era interpretations of Title IX, seek public comment on Title IX rules and create new federal regulation to better serve schools and students.

Citizen-rights groups, like the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), applauded the change in policy believing it a first step to increasing the equity of Title IX investigations.

Other organizations, like the National Women’s Law Center, worry the new guidelines will insulate the culture of sexual violence on college campuses.

RELATED: Lawsuit claims UA football players gang-raped students and staff members

Colleges given more choices when investigating sexual assault, Title IX violations

The Obama administration found that sexual violence on college campuses is vastly under reported and nearly 20 percent of women at colleges are victims of attempted or actual sexual assault. These statistics prompted the administration to take action.

In 2011, the Obama administration released a “Dear Colleague” letter through the Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights.

The letter laid out college’s responsibility to respond to reports of sexual violence quickly and fairly under the enforcement of federal regulators. A follow up letter in 2014 outlined in detail the practices and policies colleges should take to bring themselves into compliance with Title IX and combat sexual violence on their campuses.

Colleges no longer must abide by these guidelines and procedural mandates, as Secretary DeVos rescinded the policies and released new interim guidance that provides colleges more options on how they enforce Title IX compliance on campus.

These new measures will remain in place until federal regulation is passed after public comment and expert opinions are obtained.

Under the Obama era guidelines, Title IX investigations were required to use the ‘preponderance of the evidence’ standard when investigating complaints of sexual discrimination.

This standard is often used in cases of civil law, like Title IX or Code of Conduct violations on college campuses. The standard requires a lower degree of certainty that wrongdoing occurred compared to the clear and convincing evidence standard, often used in criminal trials.

The new DeVos guidelines label schools using either of the two standards as complying with their obligations under Title IX.

Both the DeVos and Obama guidelines require schools to provide equal rights to the person filing the complaint of sex discrimination and the individual under investigation. Both parties must be informed of the investigation and have a right to present evidence to an investigator and provide witnesses.

While the Obama guidelines extended both parties the right to appeal an investigation’s decision and recommended disciplinary actions, the DeVos guidelines allow schools to only provide individuals under investigation an appeal.

The Obama guidelines recommended not allowing direct cross-examination, where an individual under investigation can directly challenge or question the person who filed the complaint against them as part of an investigation.

The DeVos guidelines recommend allowing cross-examination and require both parties be given the option.

Obama guidelines prevented schools from attempting to mediate sexual violence complaints without an investigation, the DeVos policy allows colleges the option of mediation if voluntarily agreed to by both parties.

The Obama and DeVos guidelines differ on issues of investigation time-frames, confidentiality and on interim measures to protect individuals who report Title IX violations.

Schools still must provide individuals information on Title IX rights and investigation procedures. They must investigate complaints of sex discrimination and sexual violence with the permission of the individual who filed the complaint.

Schools must take prompt and effective steps to end sexual misconduct on campus.

A win for due process advocates

When the Obama administration initially released its policy, individual-right groups criticized the administration for attempting to directly control Title IX investigation procedures without receiving public or legislative input and for jeopardizing the rights of those under investigation.

“The April 4, 2011 ‘Dear Colleague’ letter had several provisions that FIRE and other due process advocates believe made it harder for students to receive fair hearings in sexual misconduct cases, and increase the risk of erroneous guilty findings,” said Susan Kruth, a staff attorney at FIRE, in an email.

Kruth pointed out that many campuses do not guarantee the presumption of innocence, the right to cross-examine witnesses, the right to an an attorney and other procedures she said safeguard student and faculty rights during investigations.

“At some schools, a heightened standard of proof like ‘clear and convincing evidence’ was the only meaningful protection accused students had against erroneous guilty findings,” Kruth said.

Organizations, like FIRE, pushed back against the new policies based on these perceived due process violations, culminating in their annulment by the Trump administration.

FIRE’s efforts, according to Kruth, are not meant to undermine Title IX or condone sex discrimination.

“It is clear that sexual harassment and assault do happen, and no matter how often they happen, schools should be working to reduce the problem and take complaints seriously,” Kruth said.

According to Kruth, schools should not impede due process rights during their investigations, as these two beliefs are not incompatible.

“It is also important to make sure accused students receive a fair hearing so that they are not punished when they committed no wrongdoing,” Kruth said.

Kruth hopes future federal regulation is created in a public arena and takes into account her concerns regarding the rights of those under investigation and also allow for the continued enforcement of Title IX on college campuses.

Culture of sexual assault still a concern

The prevalence of sexual violence on college campuses is a concern for administrators and students alike.

Three years ago, the Associated Students of the University of Arizona launched the “I Will” campaign on campus. Its aim was to end “rape culture by raising awareness of sexual assault and promoting consent” according to their campaign material.

The campus wide effort, organized alongside the Dean of Students Office and others, has spotlighted the prevalence of sexual assault on college campuses. 1 in 4 women and 1 in 20 men reported being the survivor of an assault while in college, according to the material.

“As students, it is our responsibility to step up and speak out against sexual assault and sexual violence,” said ASUA President Matt Lubisich in an email to students.

Many are concerned that these Title IX changes may impede the investigation, and punishment, of instances of sexual violence on college campuses.

By creating a hostile environment for victims to come forward, these changes could perpetrate under-reporting of these crimes and make them harder to eradicate, according to a 2017 press release by Elizabeth Tang, a fellow for Equal Justice Works at the National Women’s Law Center.

According to Tang, DeVos’s new policies give the advantage to those accused on sexual violence during an investigation.

“People like DeVos like to pretend that Title IX is a criminal law that requires ‘clear and convincing’ or even ‘proof beyond a reasonable doubt,’ Tang wrote in the same press release.

But according to Tang, Title IX is a civil law and victims of sex discrimination should not be required to meet a higher standard of evidence than a wrongful death case at a university.

Investigations cannot result in prison sentences, only administrative consequences, like suspension or firing. The clear and convincing evidence standard is a disproportionate standard to the punishments available.

“These rules also has really damaging consequences for survivors of sexual harassment and violence,” Tang wrote.

The new policies let colleges allow only the individuals accused of a Title IX violations to appeal an investigation’s decision, wave the recommended 60 day investigation time frame, and recommend allowing direct cross-examination between the accused attacker and accuser during an investigation, Tang said.

These all create an obvious hostile environment for victims bringing a claim of sexual assault, according to Tang. She worries they will make individuals feel their claims will ignored even though the vast majority of such complaints are true.

“The result is that fewer survivors may file a complaint in the first place,” Tang wrote.

With an epidemic of under reporting and many Title IX complaints not having sufficient evidence to become investigations, Tang and other believes these new Title IX changes could further exacerbate sexual violence on college campuses not play a role in combating them and punishing those accountable.

RELATED: Coaches contracts come under scrutiny at regents meeting

Colleges awaiting more permanent regulation

After the release of the new DeVos guidelines, UA President Dr. Robert Robbins acknowledged the change and told faculty and staff in an email that UA remains committed to creating a safe environment for all its community members.

“The University has implemented policies, protocols, and education programs to prevent sexual violence and effectively respond when it occurs. Those efforts will continue,” Robbins wrote.

As the anniversary of the DeVos changes approach, colleges appear to be waiting for permanent federal legislation to change their policies.

According to Mary Beth Tucker, UA’s assistant vice president of human resources consulting and equity compliance, who oversees Title IX compliance at the university, the UA has not changed how it investigates complaints of sex discrimination and sexual assault on campus.

“We have an equitable process wherein both parties have rights and the opportunity to provide evidence, statements, witnesses, and whatever information they want to provide as part of the investigative process,” Tucker said.

When a student is accused of violating the university’s Code of Conduct, which includes provisions against sexual assault, the Dean of Students Office investigates the claim.

When a member of the university staff, faculty or contractors are accused of violations of UA’s nondiscrimination and anti-harassment policy, which encompasses Title IX, by a student or fellow staff member, the Office of Institutional Equity is responsible for investigating the complaint Tucker said.

The Office of Institutional Equity provides individuals with information on their rights and services such as counseling. It can conduct an investigation into violations, taking steps to protect individuals who file a complaint in the interim. This is also true of the Dean of Students Office.

“There is no time limit for coming forward to report a Title IX concern, or to seek resources or support,” Tucker said.

According to Tucker, the number of investigations conducted by the office varies from year to year. The Office of Institutional Equity can make recommendations on employment status to supervisors and recommend sanctions if they find individuals violate university policy.

Beyond investigations, the Office of Institutional Equity, which is internal to the university, pursues proactive and preventative policies to create a safe and welcoming environment on campus.

“We want to spend the majority of our time on prevention and answering questions, fielding calls and providing clarification, guidance or support,” Tucker said.

There is not one best way to reach out to the Office of Institutional Equity to ask questions or file a complaint, Tucker said. She encouraged individuals to visit the Title IX website and the OIE website , call (520-621-9449), email or visit their office on the ground floor of the University Services building.

As for future federal regulation, Tucker welcomes the guidance to increase predictability and security.

“Clear federal guidance is always welcome. It keeps us efficient, it allows people to predict what will happen, it puts students in a position where they know what to expect,” Tucker said.

Tucker does not know of any colleges that have actually changed their policies in response to DeVos’s new guidance. Tucker and others are wondering what concrete changes future legislation will bring.

The DeVos guidance offers a window into the Trump administration’s priorities in Title IX reform. While some believe these changes will improve equity in campus sexual investigations, others worry they will prevent universities from holding individuals accountability for sexual misconduct and perpetuate a culture of ignoring victims.

As colleges decline to alter their current policies, only the passage of federal regulations will reveal the true impacts of the Trump administration’s philosophy on combating sex discrimination and sexual assault on college campuses.

Follow Sharon Essien and Randall Eck on Twitter