A panel of faculty and teachers from the UA and the Tucson Unified School District defined and defended ethnic studies in a public forum Saturday morning.

More than 160 teachers, parents and students filled Kiva Auditorium in the Education building to listen to the discussion on Arizona’s new ethnic studies law co-sponsored by the Arizona State Museum and the UA College of Education.

“”You are my other me. If I do harm to you, I do harm to myself. If I love and respect you, I love and respect myself,”” Curtis Acosta, a Chicano literature teacher at Tucson High Magnet School, said. He cited a study that concluded that, from 2004 to 2010, high school students who took Mexican-American studies courses were more likely to pass the Arizona Instrument to Measure Standards test than those who did not.

Sponsors of the bill, along with Superintendent Tom Horne and Deputy Superintendent Margaret Dugan, were invited to the forum, according to Beth DeWitt, program coordinator at the Arizona State Museum, but they declined due to campaign commitments or other schedule conflicts.

Gov. Jan Brewer signed the ethnic studies law, Arizona House Bill 2281, last May. The bill prohibits a public or charter school from having classes that “”either promote the overthrow of the United States government or promote resentment toward a race or class of people.”” It also prohibits classes designed for a particular ethnic group or that “”advocate ethnic solidarity instead of treatment of pupils as individuals.””

H.B. 2281 only affects public and charter schools overseen by the Arizona Department of Education, so the bill does not directly affect UA courses. However, UA panelists expressed concerns over its potential impact on their students and courses.

Robert A. Williams, E. Thomas Sullivan Professor of Law and American Indian Studies & director of the Indigenous Peoples Law and Policy Program, expressed concern about the effect of the bill on his students. He asked guests to think of a famous Indian chief and to raise their hands if they were thinking of Geronimo, Sitting Bull and Cochise. Most raised their hands.

“”For those of you who have your hands up, how many of you can name the chairman of the Tohono O’odham Nation? How many can name the president of the Navajo Nation?”” Williams asked. Two and three hands were raised. “”That’s what happens when you don’t have ethnic studies. … Imagine now that you’re a jury that I have to talk to to defend Indian rights and the only Indian chief you knew killed white people.””

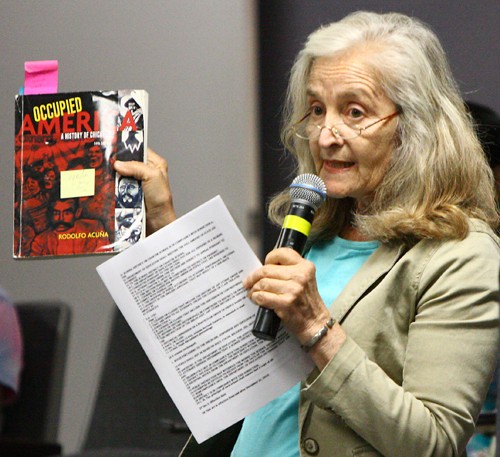

Most audience members asked about how the law would affect their children’s education and about the future of ethnic studies. One person, however, expressed support for the law and raised concerns about the use of “”Occupied America”” by Rodolfo F. Acuña in Mexican-American cultural classes taught at Tucson High School.

“”I feel very strongly that we should not be teaching hate and revolution in our schools,”” Laura Leigh, 64, said in an interview after the forum. She cited anecdotes where students and their parents were beaten or shot at by students who took Raza studies classes.

“”You can teach history as history. But when you start saying, ‘kill the gringo’ and ‘execute all white males over the age of 16,’ it’s like saying ‘hang the wetbacks.’ You don’t want to put phrases like that in public school books. You don’t want to call people by derogatory names,”” Leigh said, in reference to excerpts from “”Occupied America.””

Jennifer Marie Uzarraga, a second-year nursing student at Pima Community College, said she “”hates”” the law. She is using Acuña’s textbook in her Chicano studies class.

“”We should have a right to know where we came from, what we learn, or what we love,”” Uzarraga said. “”I want to know where my accent came from, I want to know why I do certain things or why I talk this way, why I think this way.””