From the polar vortex to “snowpocalypse,” the climate in the northeastern U.S. has been unusually cold for the past couple of years. This increase in cold may be partly due the climate change-induced melting of the Greenland ice sheet, the second largest ice body in the world.

Stefan Rahmstorf and colleagues at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research used a reconstruction of sea surface temperatures as far back as the year 900 to show that the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation is slowing down at a rate unprecedented in the past 1,100 years. Their findings were published in a recent article in Nature Climate Change.

“The Atlantic meridional overturning circulation is the interstate highway of water movement in the Atlantic,” said Paul Goddard, a geosciences graduate student studying sea level rise on the east coast of North America. “At the ocean’s surface, water moves [heat] from the Southern Hemisphere past the equator, then along the East coast as the Gulf Stream, and finally towards the high latitudes of the Labrador, Greenland, Iceland and Norwegian Seas.”

Climate models have consistently shown that with the continued rate of greenhouse gas emissions, the AMOC will slow down over the next century, Goddard said. Rahmstorf and co-authors used sea surface temperature data to indirectly demonstrate the strength of the AMOC over time.

The authors attribute weakening of the AMOC, in part, to glacial land melting, which has melted due to sea and land temperature increases.

“This increase in freshwater [from the Greenland ice sheet] also decreases the density of the surface waters, making [the AMOC] less likely to sink,” Goddard explained.

Sinking is necessary for the current to circulate water back through the Atlantic, Goddard said.

The AMOC transports heat to the subpolar and polar North Atlantic, which is released to the atmosphere with substantial impacts on climate in surrounding areas, explained Xubin Zeng, an atmospheric sciences professor, director of UA Climate Dynamics and Hydrometeorology Center and Agnese N. Haury chair in environment. As the AMOC continues to slow down or even potentially halt, there will be less heat brought up to the North Atlantic, making the surrounding areas colder, Zeng said.

“[As the AMOC slows] the impacts will be large, such as the shift of the tropical rainfall belts, additional sea level rise around the North Atlantic and disruptions to marine ecosystems,” Zeng said. “For instance, you can think of the impact of 12 feet of snow this past winter on the economy of Boston and on the residents there.”

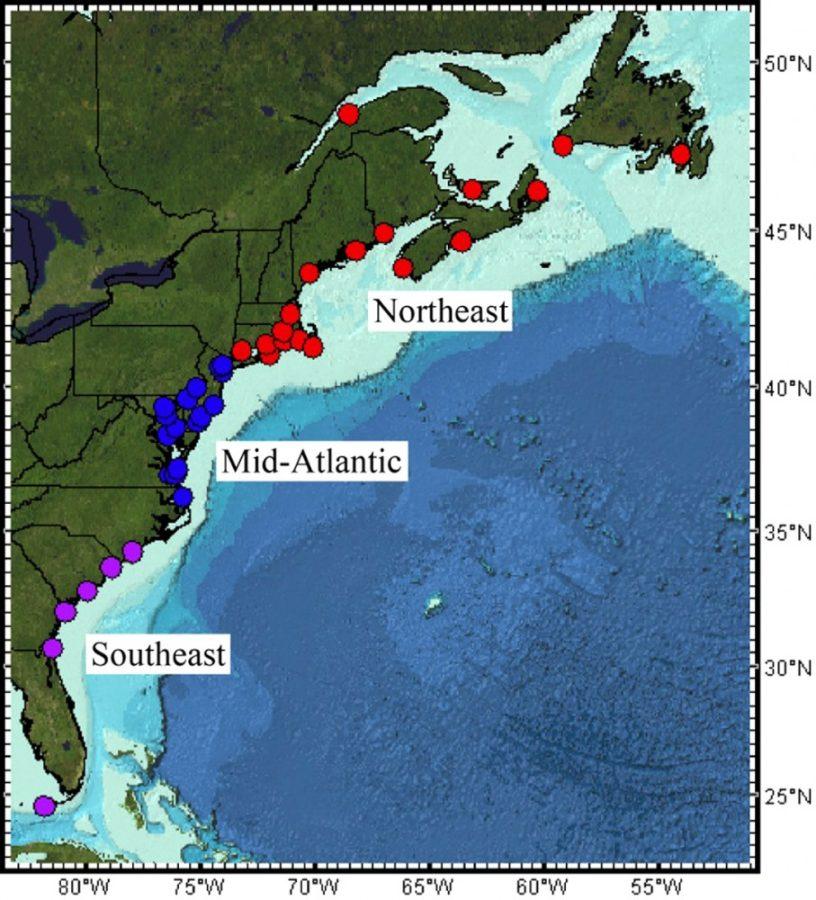

Goddard’s research focuses on explaining the 4-inch increase in sea level rise along the northeastern North American coast during 2009-2010. This finding was discovered through analyzing tide gauge data, which, in part, was explained by a 30 percent downturn in the AMOC during this time period.

Many climate change impacts are results of numerous feedbacks occurring throughout each environmental system, Goddard said.

“There are numerous processes contribute to sea level rise around the world, [making this issue a complicated problem],” Goddard said. “To ‘reverse’ the impacts of climate change, we must not only reduce our emissions, but essentially halt them all together.”

_______________

Follow John McMullen on Twitter.