A bit overindulgent, but unconventional enough to keep it from mattering, “Moneyball” takes what could have been a tired premise and delivers a surprisingly meditative take on the significance (and eventual irrelevance) of human achievement.

Surely not without a sense of irony, director Bennett Miller (“Capote”) turns in a film about baseball less likely to appease actual fans of the sport than it is to resonate with audiences on an intellectual plane.

Those looking for action beware: Of its 133-minute running time, “Moneyball” spends maybe 10 on the baseball field. But those paying attention won’t mind; the film, about Oakland Athletics general manager Billy Beane’s struggle to carve a winning team out of a stunted budget, is more a story of backroom politics and a study of the game itself than it is a retelling of the Athletics’ now legendary 2002 winning streak.

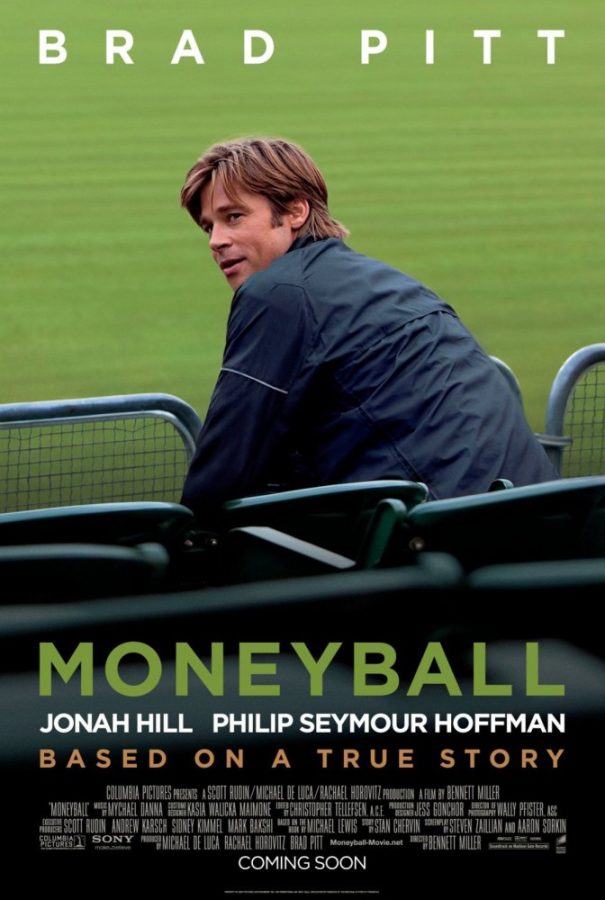

Beane — played by a refreshingly self-analyzing Brad Pitt — is out of faith, crippled by the loss of his three star players (Jason Giambi, Johnny Damon, and Jason Isringhausen) to higher-paying teams. He finds hope in Yale-educated youngster Peter Brand (Jonah Hill), whose theory that a winning ball club can be bought for a fraction of the Yankees’ budget is exactly the buoy Beane has been searching for.

Writers Steven Zaillian (“Schindler’s List”) and Aaron Sorkin (“The Social Network”) cater to neophytes of the sport without being patronizing, presenting Brand’s theory — that players with the right statistics, not necessarily the best ones, can make a winning team — in a way that’s equal parts digestible and complex.

Sorkin’s touch is especially visible throughout, particularly in the heated dialogue between Beane and his veteran team of scouts.

Also excellent (as usual) is Phillip Seymour Hoffman, whose portrayal of Athletics’ manager Art Howe makes for the very best kind of antagonist: Hostile yet sympathetic, likable despite himself. His scenes with Pitt are among the best in the film.

The movie’s only fault is in its intemperance — like so many paintings, it becomes clear toward the end that Miller appreciates what he’s created and, to his own detriment, doesn’t quite want to put the brush down. Though as a whole, the film doesn’t suffer much from this.

“Moneyball” is two solid hours of cinema, capped by a forgivably excessive 15 minutes that, in the grand scheme of things, does little to detract from what otherwise proves to be a thoughtful, emotionally resonant study of character.