In the middle of the exhibit hall at the University of Arizona’s Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research stands a 4,000-pound sample of a Giant Sequoia that began its growth in 212 A.D. and fell in 1915.

The laboratory houses over 2.5 million wood research specimens in its archive for study.

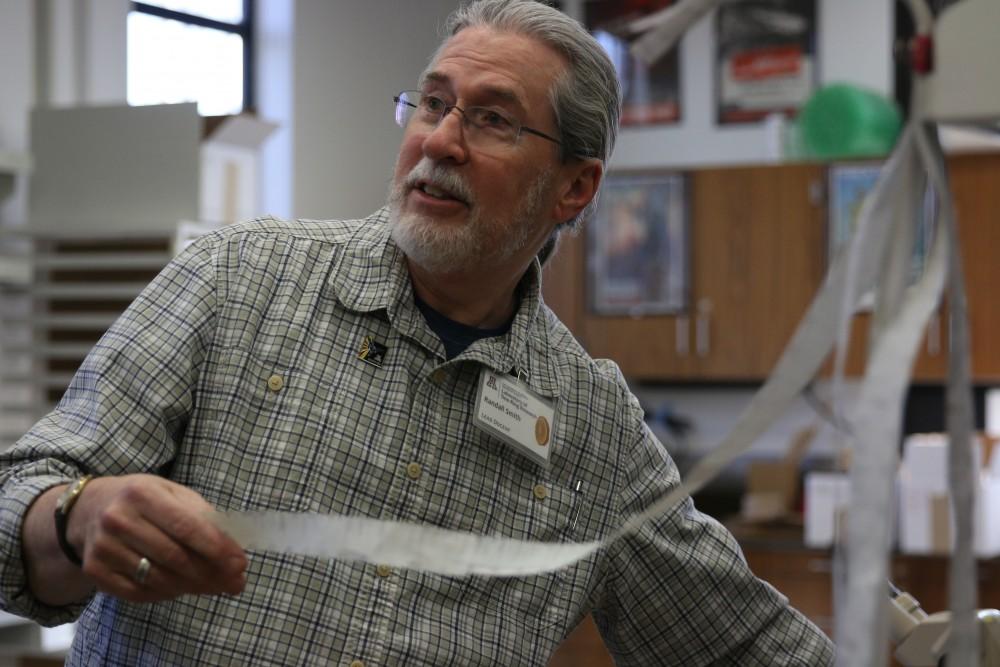

There are multiple labs in the center, each focusing on a certain study within dendrochronology, like chemistry or anthropology. They all aim to educate the public, as well as do research to better understand climate and history, according to Randall Smith, the lead docent at the lab.

“It takes years and years to reach from beginning to end,” Smith said. “That’s why my big concern with the program here is how do you communicate science to the public.”

The laboratory’s main mission is to remain in the forefront of world dendrochronology through the use of tree rings as natural chronometers and recorders of change in the environment, according to its website.

RELATED: Annual Undergrad Biology Research Program conference brings together minds, bodies and souls

The lab has graduate students using dendrochronology, the dating and study of annual rings in trees, to create a dated history of environmental factors all over the world. The students all come from different areas of study, including geography, chemistry, astronomy, physics, biology and more.

The lab is not an academic branch of the university, meaning that you can’t get a degree in dendrochronology, but the students do their lab work and research at the center to get an understanding about the history of the environment around the world.

In order to inform the public on the “unique science culture” the lab brings to campus, Smith runs tours and educational experiences

“What we’re all about is helping people see the big picture and [educating public on environment],” Smith said.

The tour starts in the exhibit hall, talking about the history of the research and the importance of the science in the building.

“About 10 years ago, we were asked by archeologists in Indonesia to date the Tambora eruption because the international dateline didn’t exist then and affected the whole planet,” Smith said. “We use two things: the measurement of the changes in the upper atmosphere and trees, so we were able to identify volcanic eruptions from long before Tambora using preventing data.”

This is one of the many ways the research scientists used data collected to help identify environmental history and create a climate timeline.

RELATED: UA’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory showcase an out-of-this-world art exhibit

This data all comes from wood samples. A researcher collecting a sample uses a device, called an increment bore, to drill into the tree by hand and retrieve a small sample. This is done very carefully so the tree isn’t harmed.

“[You] don’t need to drill from the outside of the tree all the way to the center to get his life story,” Smith said.

The tree will cover the hole created by the sample when it grows, and a small sample is far more efficient than cutting the tree down, according to Smith.

“When [the sample] comes out of the tree, it’s still living tissue,” Smith said. “The trick is to get it back to the lab without breaking.”

After collection, the sample goes to the wood shop across the street, where it gets polished and mounted for research. Then, the lab researchers can start to date the rings of the tree.

“[I] compare it to the other trees that I’ve already looked at, and I can not only tell how old that tree was just by looking at a sample of it, but I can also tell you how old other trees are by making comparisons to it,” Smith said.

The researchers take pure cellulose from the tree to do a chemical analysis. They put it through a mass spectrometer, then send the chemistry report back to the tree-ring lab. A chemist on the fourth floor of the building interprets it to figure out how much rainfall the certain area received that specific year.

This report also shows how much CO2 there was in the area, what the atmosphere was like and the amounts of nitrogen and oxygen isotopes around that tree in each year. Researchers obtain a thorough understanding of the tree’s history, which helps build that chronology of climate zone records to identify patterns and pinpoint environmental conditions.

“I know the weather in fall 1925; I don’t know the rainfall in the year 620, but now I’ve got a calibration that works, then I’ve developed it for this climate zone, and then the more trees I add to it the more accurate my results get,” Smith said.

John Keck, a first-year Ph.D. student at the UA, works specifically with samples that focus in the Mediterranean area to fill in gaps in the chronological record.

“The things [data] that the wood tells us about what people did in the past is really incredible, and I can tie a piece of wood that we had sent to us that has a characteristic signature that says all these things about people in the past,” Keck said. “This is pretty cool; that’s the kind of thing we like to work on in this lab.”

The lab holds Docent-led tours on the following dates:

- Second Tuesday of the month (August through May) at 10 a.m.

- Third Wednesday of the month (August through May) at 10 a.m.

- Fourth Thursday of the month (August through May) at 2 p.m.

The Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research is located at the Bryant Bannister Tree-Ring Building, 1215 E. Lowell Street.

Follow Pascal Albright on Twitter