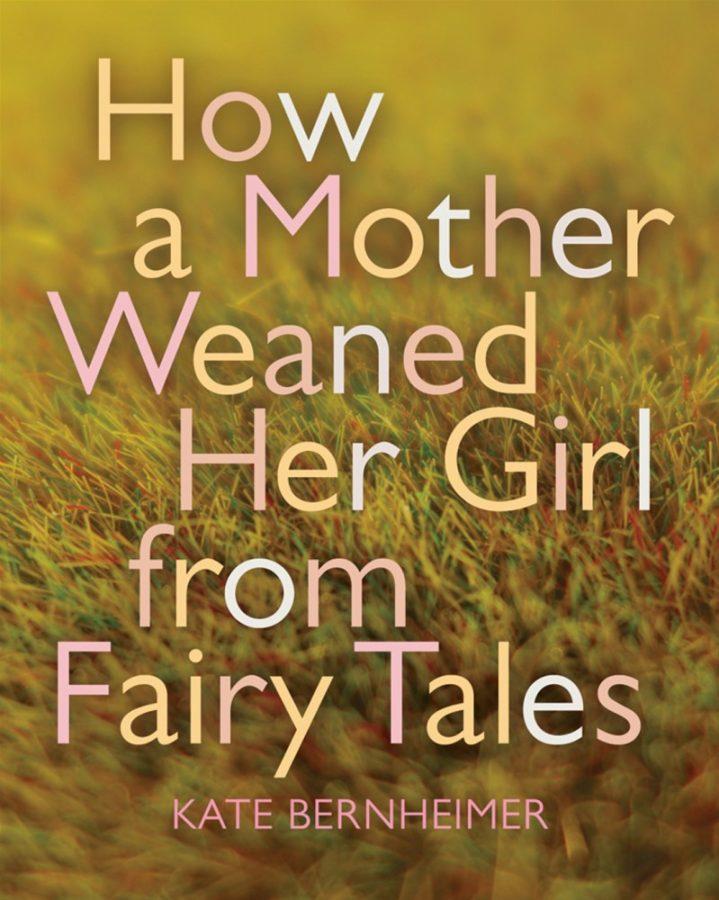

Nights where parents read fairy tales to their children before bed or those moments spent pondering why holding a book is so profound are over. The UA Poetry Center brings to you new works by two UA English professors on Thursday from 7-8 p.m.: Ander Monson’s “Letter to a Future Lover” and Kate Bernheimer “How a Mother Weaned Her Girl from Fairytales.” The Daily Wildcat caught up with them before the reading to talk.

Daily Wildcat: How did you start writing?

Bernheimer: It was a great love of reading that led me to write stories. I love the freedom, safety and adventure of stories — first, and still foremost, as a reader.

Monson: When I was in what would have been third grade, maybe, I wrote a review of the “Hardy Boys: The Crimson Flame,” and my teacher liked it so much that she passed it along to the local newspaper, who published it. But they didn’t know that I copied the text from the back of the book, so it was completely plagiarized, and I wondered if my first publication at age 8 being the plagiarism gave [me] the taste for [writing]. Since then, I’ve stopped plagiarizing.

Is there a noticeable difference between writing, fiction, nonfiction and children’s fiction?

Bernheimer: Maurice Sendak, who wrote so many great books, including “Where The Wild Things Are,” said, “I don’t write for children. I write.” It’s the same for me. When I write fiction, I’m just writing; the audience comes after the fact.

Monson: There’s a huge difference. The job of nonfiction is largely informative, but it has to be entertaining, too. To me, nonfiction is always about the world first, whereas fiction is about characters first. They’re different, but sometimes they overlap a lot.

What made you decide to teach, and how has it been helping students understand your passion and writing?

Bernheimer: Like writing, I came to teaching out of a love of reading. Teaching is a way to talk about books around the clock — books and life and problems and dreams. I can’t imagine my life without students, who offer me so much hope and inspiration. I love opening students up to the diverse world of fairy tales, with its strange history; there’s something for everyone there. And perhaps the biggest thing this offers is a chance to have real conversations about serious things in a compassionate, intelligent, sometimes dark but often hilarious manner. It’s a gift to teach fairy tales.

Monson: When I was in graduate school, I had a job offer for a teaching job, and I had a job offer for publishing. I kept those two balls in the air a while. Then I realized I like being part of the academia, the university community and students who have interests and who are excited about writing and reading in a way that the larger culture isn’t always excited about it. I ended [up] saying yes to the teaching and no to the publishing, because there seem to be more life [in teaching]. A lot of what I think of my job as a teacher is to not familiarize students with the genre of what they’re writing but trying to get to push people out of their comfort zones and what … you care about as a writer.

What would you like people to take away from your passions and writing?

Bernheimer: I faced obstacles early in my career, because writing fairy tales was very out of step in mainstream literary circles. A big part of my teaching is to communicate that you should stick with what you love, not let anyone take it away from you or tell you it’s not cool or worthwhile. It’s crazy that my professional life consists of reading, writing and talking about fairy tales! You can make a life from doing what you love, if you have patience, work hard, are kind — and encounter a big dose of good luck. Stranger things happen.

Monson: What I hope is that they’ll see that it’s a participatory process. I mean, even reading is a participatory process. If you reread a book when you where 15 and read it now, you’ll feel very differently about that book because you’re different. Part of what I’m interested in, in my new books, is thinking about the ways in [which] readers interact with books and with writers. It’s not a one-way process … unlike, say, with PDFs or e-cards. … Books have history, and we interact with them in ways that are very personal and intimate.

_______________

Follow Ivana Goldtooth on Twitter.