Do you remember the last time you enjoyed a plate of shrimp scampi or shrimp tacos? There’s a good chance one of those shrimp’s relatives paid a visit to the University of Arizona campus before it made it to your plate.

The UA Aquaculture Pathology Laboratory is the only World Organization for Animal Health Reference laboratory for crustacean diseases in North America.

This means shrimp researchers and farmers from nearly every shrimp-producing country in the world have had some sort of interaction with the lab, said Arun Dhar, director for the lab and associate professor of shrimp and other crustacean aquaculture.

The U.S. imports close to $6 billion in shrimp every year, but exports far less, Dhar said.

“We really don’t produce shrimp, but we develop tools and technologies in order to make shrimp farming sustainable,” Dhar explained. “In other words, we export technology, knowledge and expertise to the world.”

A global need

The UA Aquaculture Pathology Lab is one of these top exporters of research and expertise. The lab provides everything from disease diagnostics to quarantining of wild-caught breeding stock to valuable training courses and proficiency tests.

These services are in high demand because any shrimp or shrimp feed being exported from the U.S. needs to be certified as disease-free, Dhar said. When an outbreak occurs in this country, all shrimp must be checked before being exported.

Nearly all of the currently known shrimp pathogens have emerged in the last 40 years, according to Dhar. This is primarily because of a global shift from subsistence farming to industrial production of shrimp.

“Anytime a farming practice becomes more industrialized, you are growing animals at a much higher density and the probability of an outbreak of diseases is much higher,” Dhar said.

It is for this reason that the lab is located in the Arizona desert, miles away from any major body of water.

“If you are doing research on shrimp diseases and your lab is located next to the ocean, then the probability is high that the disease might spread,” Dhar said. “Anytime you work on infectious diseases, you really like to have your lab away from water.”

RELATED: UA course helps rugby ream with nutrition education

Wet lab

Despite this, the lab does run an off-campus wet lab facility, separate from the diagnostic labs.

The wet lab is in charge of all the live shrimp research. This can involve training industry professionals, conducting studies, testing feed additives, developing protocols and quarantining shrimp stocks, said Brenda Noble, senior research specialist at the Aquaculture Pathology Wet Laboratory.

When shrimp farmers are picking shrimp for a breed stock, they want to know if they have any inherent genetic resistance to common pathogens, Noble said. If the results from tests performed at the wet lab prove the shrimp are in fact resistant, farmers can use them to improve the genetic resistance of their shrimp crop.

Diagnosing the disease

There’s more than one way to skin a cat, and there’s more than one way to diagnose a shrimp, too.

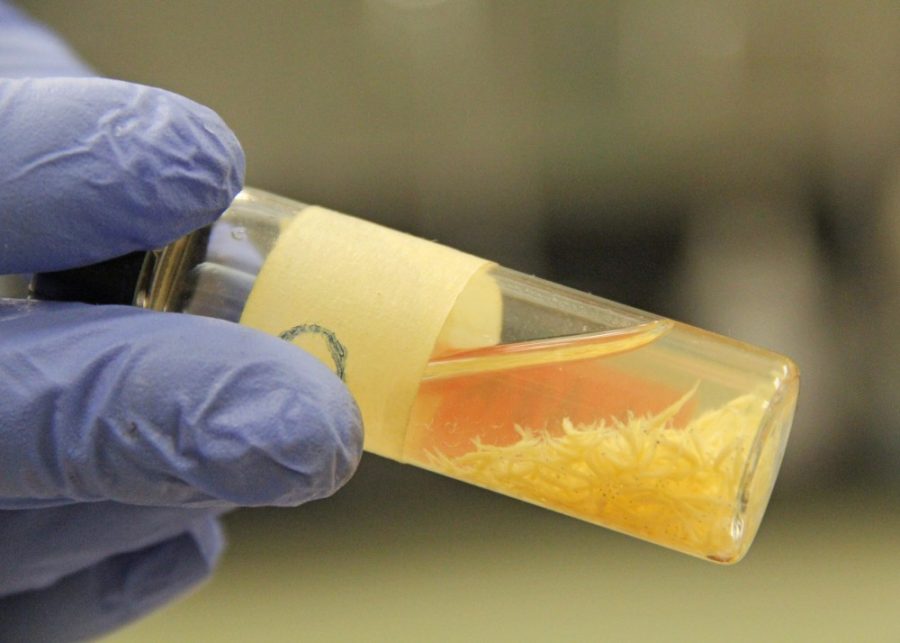

When a client wants to diagnose its shrimp, it can either send them to the histology lab for tissue testing or to the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) lab for DNA extractions, said Jasmine Millabas, histology specialist at the Aquaculture Pathology Histology Laboratory.

While PCR is more popular with clients because it often produces results faster, histopathology is necessary for diagnosing diseases, Millabas said.

In the histology lab, Millabas starts by dissecting the head and tail sections from the diseased (and deceased) shrimp and placing them into cassettes.

After being dehydrated in a processor overnight, the individual cassettes of shrimp tissue are coated to form wax blocks. These wax blocks can be easily sliced into thin sections and placed on glass slides, Millabas said. These slides represent microscopic cross-sections of the shrimp’s diseased tissue.

Millabas then melts the remaining wax from the tissue and puts the slides through a series of chemical stains. These stains will help the histopathologist read the tissue and diagnose the shrimp’s disease.

RELATED: Grant helps Navajo Nation combat resource scarcity with STEM

Polymerase chain reaction lab

In the room next door, Mike Rice, an animal-biomedical sciences research specialist, works on diagnosing shrimp using the PCR method.

“PCR is a method to amplify DNA, so if the crustaceans have either a bacterial or viral infection, we can detect the DNA from those viruses or bacteria,” said Rice, PCR specialist for the lab.

While both labs can effectively detect diseases in shrimp, they are distinctly different in their methods, Millabas said. Rice said one way was in the timing.

“You might be able to say that with PCR you can detect some things sooner, before [the disease] starts to show up,” Rice said. “In theory, with PCR you only need one bacterial cell or virus, so you can detect the whole infection before it gets going.”

Top-of-the-line training

Because there is a global demand for the research done in these labs, once a year the UA offers a week-long shrimp pathology course.

For six days, participants are immersed in the lab experience, receiving enhanced hands-on training. In the last 27 years that the lab has offered the course, it has trained nearly 1,400 people, Dhar said.

This year, there were 19 participants from across the world, ranging from Australia to Thailand to Canada, according to Millabas.

Along with the short course, the lab also administers a proficiency or “ring” test to shrimp diagnostic labs around the world.

“We send infected shrimp tissue carrying specific diseases to these labs without telling them what they are, and then the labs must try to diagnose them correctly,” Dhar said.

According to Millabas, this helps the other labs to determine how efficient they are and where they might need to improve, but it also helps the UA lab ensure they’re doing top-of-the-line work.

It’s this standard of work that’s earned the UA lab attention and respect from some of the top producers in the shrimp industry.

“For me, it’s a privilege and an honor to run this lab, and I’m very proud of the lab and of my colleagues,” Dhar said.

Follow Hannah Dahl on Twitter