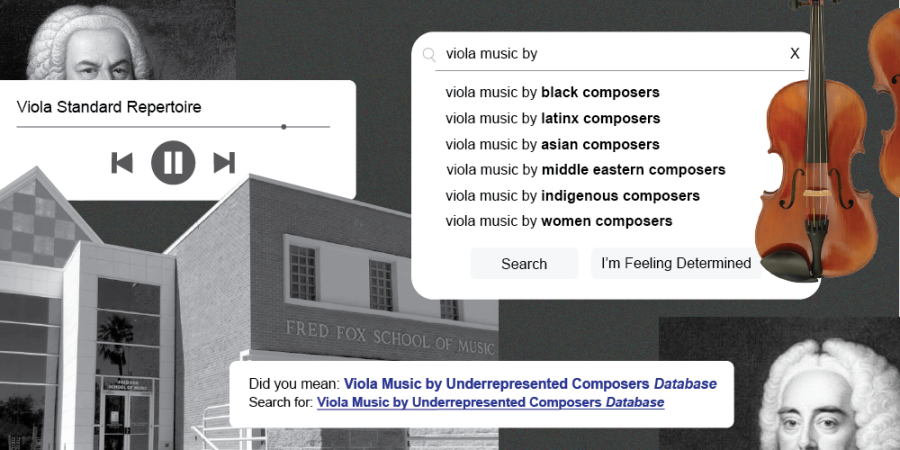

This month, University of Arizona viola professor Molly Gebrian published a database of pieces for viola created by underrepresented composers. The database contains over 1,100 composers and compositions, all of which were created by Black, Indigenous, Latinx, Middle Eastern, Asian or women musicians. Right now, the list is available on Google Sheets, but later this fall, it will be available on the American Viola Society’s website as a searchable database.

Gebrian was inspired after the nationwide Black Lives Matter protests started in late May when, as she put it, the classical music world “woke up” to an issue they’ve been dealing with for many years: the fact that most music that’s played is composed by white men.

“I didn’t know a lot of viola music by Black composers or Latinx composers or women composers,” Gebrian said. “Many times I’ve wished there was some database where I could go and look up ‘compositions for viola by Black composers’ and then I was like, ‘Wait a minute, I could make that database.’ I’ve been waiting for somebody to do this; I’m somebody. I could do this.”

RELATED: 9/11 Tower Challenge honors fallen first responders

However, this project was a huge undertaking and Gebrian enlisted some of her students and colleagues to help her with research and data collection. Her team included undergraduate viola performance majors Dorthea Stephenson and Katie Baird, UA alumna Adie Cannon and violists and librarians Joshua Dieringer and David Bynog.

Together, along with the help of some viola professors from around the United States and abroad, the team researched, collected and purchased hundreds of pieces of music from all over the world and from the past 80 years.

According to Gebrian, while all of the compositions are for viola, the database includes arrangements for viola and piano, for duos and trios with violas and for violas accompanied by an orchestra. Pieces listed on the database also have information on where users can purchase the piece, where they can listen to a recording (if one exists) and where they can check it out at a library (if the piece is available for checkout).

When the team started the project, their goal was to find 500 pieces by women, Black, Indigenous and people of color composers. Baird went into the project assuming the team would find very few compositions.

“The viola repertoire is super little compared to the violin and cello,” Baird said. “[But] in two months, we were able to find 1,100 pieces for viola.”

Gebrian and her colleagues hope that the database will make it easier for students, performers and programs to access and incorporate music from underrepresented groups into their repertoire.

“A lot of professors don’t know any music that is by not dead white guys or know very, very little. It’s hard to teach something you don’t know anything about,” Gebrian said. “One of the goals of this database is to just help students, teachers, everybody, [know that] this music exists.”

RELATED: Postal Progress Q&A: How UA artists are fighting for racial equity one postcard at a time

For Baird, working on the database project challenged assumptions about the viola she’d had since childhood.

“Growing up, a teacher would give you two or three pieces from a standard repertoire. In my experience, we never really branched out of standard practice,” Baird said. “I never questioned that … I thought, ‘There’s just not a lot of pieces for viola, so I’ll get to learn all of them in my life.’ And that’s definitely not the case anymore.”

Gebrian knows that projects like the database are one of many that needed to make music education more diverse and inclusive.

“Really, what we need is a national overhaul of the music curriculum,” Gebrian said. “But there are more and more individuals realizing this is not okay. The status quo is absolutely not okay. And that’s how change has to start, [with] individuals doing what they can to affect change.”

However, Gebrian said she feels there are some creative ways in which professors can start incorporating music like the pieces in the database.

“I changed the audition requirements for students to join the viola studio here,” Gebrian said. “If they’re auditioning to come here and study viola that they must play at least one work by an underrepresented composer.”

In addition to this, Gebrian suggested changing competition piece requirements and concert themes to feature or focus on bodies of work by BIPOC and women composers. She also said that professors can use the music of underrepresented composers to teach the skills usually worked on with standard pieces.

RELATED: Rec Center instigates new precautions for mid-pandemic workouts

According to Gebrian, the fact that the classical music world “only performs music by dead white guys,” also contributes to an environment that is alienating for students of color.

“It’s a very isolating world,” Stephenson said. “Typically you’re the only person in the room [that looks like you]. Not only is there no one else in the room with me here, but I’m not engaged with other musicians or composers of my culture.”

Besides feeling alone, Stephenson also said that the stigma that comes with being a Black musician studying viola creates an environment that requires her to work harder to gain the respect of her peers.

“With playing the viola there’s a certain level of underestimation, but I feel that increases tenfold when you’re a Black musician,” Stephenson said. “There’s always an assumption that you’re less than. The way you command respect is through your playing. I always feel an insane amount of pressure, not to be the best, but to be better, to garner that same respect.”

While the UA music program and the classical music world both have a long way to go in order to solve these issues, the underrepresented composer database is an impressive step forward, according to Gebrian.

Stephenson is also confident that a focus on more diverse compositions will not only help with diversifying the program, but also make for better musicians.

“I think it’s really important to know these different styles because it makes you more versatile and more knowledgeable,” Stephenson said.

Gebrian hopes that this project can encourage positive change, however small, and start helping women students and students of color feel more welcome in the classical music space.

“I understand why people may feel like they don’t belong, but we need you,” Gebrian said. “We need your ideas and we need your artistry. You belong in classical music. You belong here.”

Follow Katie Beauford on Twitter